Platformers are a genre of games that involve heavy use of climbing and jumping in order to progress. Examples include Super Mario Bros, Hollow Knight, VVVVVV.

~Inspiration~

Over Thanksgiving break, I played a lot of games… maybe a little too much! This project is heavily inspired by a few games. For example, I picked up Hollow Knight which is a fun yet frustrating single-player platformer game. The sounds of jumping, using items, ambient sounds, and swinging a nail followed me to my sleep. I thought that I could try replicating some of them for my final project.

Ambient Sounds

Snowy Environment

The first piece of the sound pack I started working on were the ambient sounds. These would be used to indicate the environment the current level of the game. I began by creating a snowy feel using the LFNoise1 Ugen in a SynthDef.

At first, I had trouble configuring the audio signal to work with the envelope. At first, I only had the attack and release time defined for the percussive envelope. This caused the audio rate to be released linearly, which I did not want. Instead, I wanted the sound to be at the same sound level until the end where it should level off. To remedy this problem, I used the curve argument of Env and set it to 100 instead of the default -4.

Here’s the resulting sound clip:

Rainy Environment

Moving on to the next ambient sound I created, I decided to introduce a rainy environment. I used a similar approach to creating the instrument used for the snowy environment. Instead of using a low pass filter, I opted to use a high pass filter instead. I also changed the frequency to more accurately capture the sound of hard rainfall.

After that, I applied the reverb effect to it using the Pfx class.

Background Music

For the background music, I wanted to experiment with some orchestral sounds. It was pretty difficult trying to get a convincing SynthDef for strings, so I looked at sccode for ideas. I found that someone made some code that mapped samples to midi notes in the link here so I used that as the basis for the granular SynthDef which uses samples provided by peastman. It uses the buffer to load the instruments. Here’s the code that maps the instrument samples to MIDI notes. It’s a long block of code so you’ll have to look at the image in another tab to view it.

Now that the instrument has been defined, I decided that I want the music to have some chromatic notes to produce an unnerving sound. Something that would be played during a final boss fight. I configured it to use the default TempoClock at 60 bpm and I kept it simple with a 4/4 time signature. It is mainly in E major, but as I mentioned, there’s some chromatic notes like natural Cs and Ds. Here’s the resulting clip.

Walking

Moving on to the sounds that would be triggered by events, I started by creating the walking sound. I looked back at the sound_fx.scd file to follow this piece of advice given:

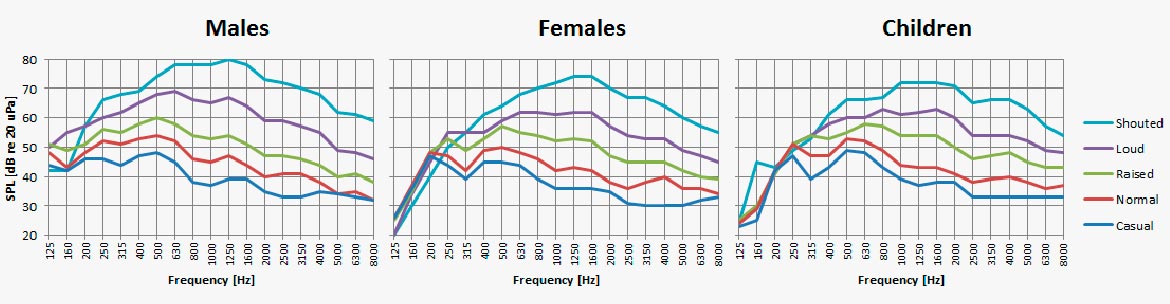

I recorded some sounds from a game and put them into ocenaudio and Audacity to use their FFT features and here were the results from ocenaudio, highlighting only the portion of a single footstep sound.

I noticed that frequencies around 1000hz and below were the most prominent, so the frequency of the footstep should probably be emphasized around there. The audio recording includes pretty loud ambient sounds, so that probably explains the higher frequencies.

I attempted to replicate this sound using a SinOsc Ugen and a Line to generate the signal. I used the Line for the frequency argument of the SinOsc because it allows me to have more flexibility knowing that a footstep does not have a constant frequency. I configured the envelope to start at 300 and end at 1, resulting in this footstep sound which I ran through an infinite Ptpar.

SynthDef(\walking, {

var sig;

var line = Line.kr(200, 1, 0.02, doneAction: 2);

sig = SinOsc.ar(line);

Out.ar([0,1], sig * 0.6);

}).add;

~soundFootstep = Pbind(

\instrument, \walking,

\dur, Pseq([0.3],1)

);

(

Ptpar([

0, Ppar([~soundFootstep], 1)

], inf).play;

)

Jumping

For the jump sound effect, I wanted to have a bubbly type of sound. I used a similar approach to the footstep SynthDef, but I made the Line rise in frequency instead of descend. Also, I made the envelope and Line sustain significantly longer.

I took note of the FFT of the jump sound from the game, but it didn’t result in the type of sound I wanted. It was really harsh so I modified the frequencies a bit resulting in this sound clip

SynthDef(\jumping, {|time = 0.25|

var sig;

var env = EnvGen.kr(Env.perc(0.01, time), doneAction: 2);

var line = Line.kr(100, 200, time, doneAction: 2);

sig = SinOsc.ar(line);

Out.ar([0,1], sig * 0.8 * env);

}).add;

~soundJump = Pbind(

\instrument, \jumping,

\dur, Pseq([2],1)

);

(

Ptpar([

0, Ppar([~soundJump], 1)

], inf).play;

)

Landing

I had a GENIUS idea of continuing to use the Line class to create my signals. You’ll never guess how I achieved the landing sound effect. Well, you might. I just swapped the start and end frequencies of the line. It ended up making an okay good landing sound, which sounds like this

I tweaked a little more and changed the end frequency to be lower at 10, which I think sounds a bit better.

SynthDef(\landing, {|time=0.1|

var sig;

var env = EnvGen.kr(Env.perc(0.01, time), doneAction: 2);

var line = Line.kr(200, 10, time, doneAction: 2);

sig = SinOsc.ar(line);

Out.ar([0,1], sig * env);

}).add;

~soundLand = Pbind(

\instrument, \landing,

\dur, Pseq([2],1)

);

(

Ptpar([

0, Ppar([~soundLand], 1)

], inf).play;

)

Picking up an item

When I brainstormed what kind of sound to give the item pickup, I thought of Stardew Valley and its sounds, specifically the harvesting. I used this as an excuse to take a break from homework to play the game for research purposes. The sound of picking up items sounded pretty simple. Here’s what I came up with using this code

SynthDef(\pickup, {|freq|

var osc, sig, line;

line = Line.kr(100, 400, 0.05, doneAction: 2);

osc = SinOsc.ar(line);

sig = osc * EnvGen.ar(Env.perc(0.03, 0.75, curve: \cubed), doneAction: 2);

Out.ar([0,1], sig * osc * 0.8);

}

).add;

~soundPickup = Pbind(

\instrument, \pickup,

\dur, Pseq([1],1)

);

(

Ptpar([

0, Ppar([~soundPickup], 1)

], inf).play;

)

Throwing away an item

For the final sound that I created for this project, I made something to pair with picking up an item. I wanted it to have a somber tone that elicits an image of a frown. The disappointment of the item being thrown emanating from itself. As sad as the fact that this class is ending. Anyways, here’s the sound!

SynthDef(\throw, {|freq|

var osc, sig, line;

line = Line.kr(400, 50, 0.2, doneAction: 2);

osc = SinOsc.ar(line);

sig = osc * EnvGen.ar(Env.perc(0.03, 0.75, curve: \cubed), doneAction: 2);

Out.ar([0,1], sig * osc * 0.8);

}

).add;

~soundThrow = Pbind(

\instrument, \throw,

\dur, Pseq([1],1)

);

(

Ptpar([

0, Ppar([~soundThrow], 1)

], inf).play;

)

Reflection

Doing this project has made me more appreciative of the sound engineering of every game I play. I now find myself analyzing the different sounds that the developers choose to incorporate and sit in thought how they made that. There’s surely some, but not many, that use programming languages like SuperCollider to synthesize such sounds. Exploring new concepts like buffers has been pretty challenging, but it has shown me that there’s a wide range of choices available with SuperCollider.

Thanks for reading my writeup. Hope you enjoyed!